Insights from Somalia | Workshop on Humanitarian Research & Innovation Futures

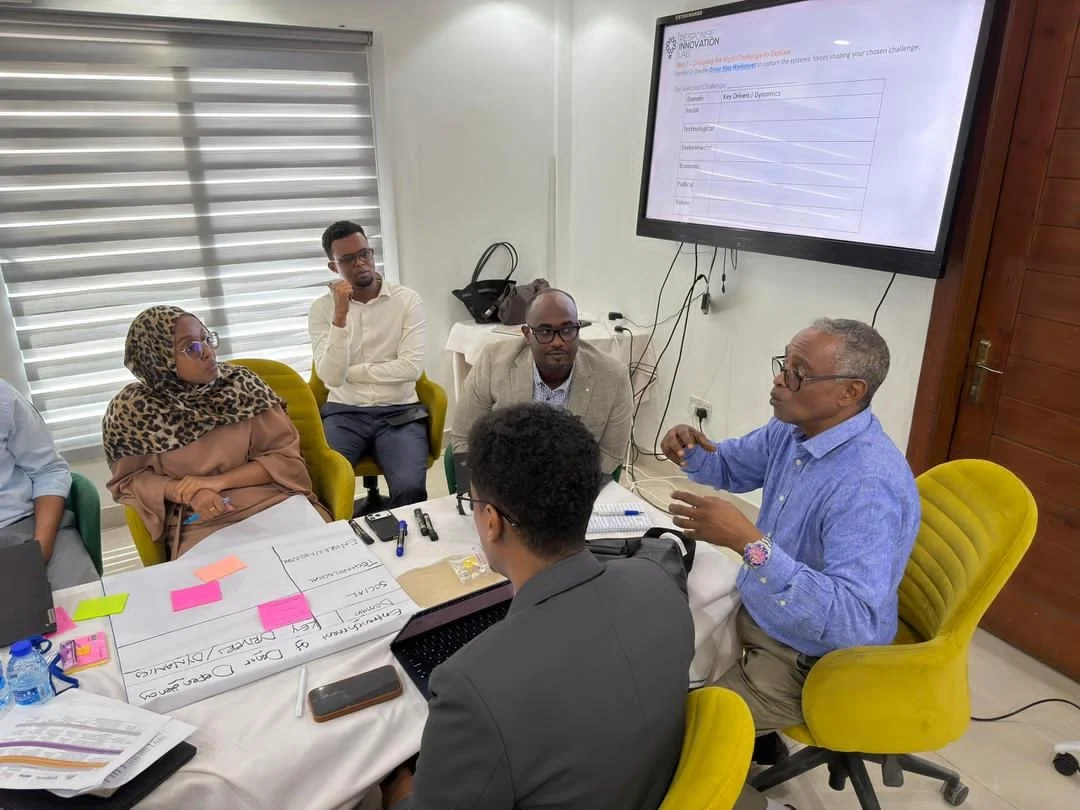

On January 6, the Somali Response Innovation Lab (SomRIL) hosted a national-level Humanitarian Research & Innovation Futures Consultation in Mogadishu , convening a diverse cross-section of Somalia’s humanitarian ecosystem to collectively shape a forward-looking, nationally grounded agenda for humanitarian research and innovation. Using Elrha’s Humanitarian Research & Innovation Futures Toolkit, the consultation applied strategic foresight methods to examine key drivers of change, surface critical uncertainties, and stress-test existing humanitarian approaches—ensuring future responses remain adaptive, evidence-driven, and locally relevant.

This blog post brings you some key insights generated from the workshop.

Through the workshop, participants identified two challenges in Somalia that should be prioritised to tackle: “entrenched donor dependency” and “failures to anticipate systemic shocks”. The main drivers across social, technological, economic, political, environmental, and values aspects can be summarised as follows:

Entrenched donor dependency

Social drivers: Prolonged conflict, displacement, and climate shocks have normalised humanitarian aid as a core social safety net. Clan and kinship systems provide everyday resilience but are perceived as insufficient for large shocks. Clan dynamics shape trust and perceptions of fairness, generating suspicion toward centrally managed funds. While local NGOs and CSOs have social legitimacy, compliance and risk requirements limit their direct access to funding.

Technological drivers: Humanitarian digital systems are primarily designed for donor accountability and risk management, reinforcing upward accountability and limiting local ownership of data and platforms. Mobile money enables efficient cash transfers but is not suited to more complex or locally governed financing mechanisms. Innovation exists but remains fragmented, small-scale, and poorly integrated, with data systems prioritising reporting over learning and adaptation.

Economic drivers: Limited domestic public finance and a narrow tax base make external grants the dominant source of humanitarian funding. A dynamic private sector and strong diaspora remittances support households but remain disconnected from humanitarian financing and collective goods. Shrinking global budgets, high operating and compliance costs, and risk aversion favour conservative, grant-based approaches and constrain innovation and long-term planning.

Environmental drivers: Recurrent droughts and floods create a “permanent emergency rhythm,” locking actors into response mode and reinforcing dependence on external funding. Climate-sensitive livelihoods and environmental degradation mean even moderate shocks escalate into system-wide crises. Barriers to accessing climate finance push humanitarian actors to rely on traditional donors for urgent needs.

Political drivers: Federal fragmentation and overlapping mandates dilute political ownership of humanitarian financing reform and localisation. Humanitarian aid operates as a parallel governance system, normalising external stewardship of public goods. Donor risk management, influenced by political and reputational concerns, results in centralised, compliance-heavy funding that entrenches dependency.

Values and norms: A strong norm of grant-based, donor-led assistance frames external aid as the most legitimate crisis response. Accountability is associated with compliance and delivery rather than learning or system change, discouraging risk-taking in practice. These norms have shifted responsibility for large-scale crisis response away from community systems toward the humanitarian sector, making donor dependency an accepted default.

Failures to anticipate systemic shocks

Social drivers: Repeated, overlapping crises have normalised crisis as a permanent condition, shifting attention toward immediate response and reducing space for anticipation. Clan and kinship systems provide everyday resilience but are quickly overwhelmed by cascading shocks. Communities hold valuable lived knowledge of emerging risks, yet this is rarely channelled into formal foresight processes. Informal risk communication, forecast scepticism, and social expectations for rapid response over preparedness further weaken anticipatory action.

Technological drivers: Early warning and risk analysis systems exist across sectors but operate in silos, with fragmented dissemination and limited integration, preventing consistent translation of warning into early action. Data systems prioritise real-time monitoring and donor reporting over forward-looking analysis and scenario planning. Predictive tools are often externally developed and poorly adapted to local realities, limiting trust and uptake. Foresight and AI-enabled innovations remain pilot-based and disconnected from core planning and financing, despite strong capacity in specific technical areas.

Economic drivers: Humanitarian financing is predominantly reactive, with resources mobilised after shocks occur and limited flexible or multi-year funding for preparedness and anticipation. Incentives favour short-term delivery over investment in uncertain future risks. Although anticipatory action mechanisms exist, they remain small-scale and constrained by donor risk and accountability frameworks, with acting early often perceived as costlier than acting late.

Environmental drivers: High exposure to climate volatility produces frequent and increasingly compounding shocks. While environmental signals are monitored, their interactions with social, economic, and political dynamics are not consistently analysed. Recurrent emergencies crowd out investment in long-term adaptation, resilience, and anticipatory systems, and climate finance frameworks are poorly aligned with operational early action.

Political drivers: Federal fragmentation and overlapping mandates hinder coordinated risk anticipation and delay the shift from early warning to authorised early action. Political uncertainty, insecurity, and rapidly shifting donor priorities discourage long-term planning. Risk-sensitive political environments favour control and compliance over experimentation, while limited institutional mandates for foresight and the political sensitivity of early warnings delay action until crises are fully visible.

Building on the identified challenges and drivers, participants formulated a set of “foresight questions” to prompt further reflection and to guide the identification of potential solutions across different time horizons.

Question 1: How might Somalia reduce entrenched donor dependency and strengthen community resilience in a future where humanitarian funding is increasingly volatile, donor priorities are shifting, and climate shocks are intensifying, so that life-saving and livelihood-support services remain continuous and locally owned during crises?

What can we do in short-term (0-12 months)? Map critical life-saving services most exposed to funding cuts and identify minimum service continuity thresholds at community and district levels; Prioritize and protect funding for resilience-building and early recovery activities within humanitarian programmes to prevent erosion of coping capacity during funding shocks; Convene donors, government, private sector, and diaspora actors to agree on shared principles for financing stability and localisation in a context of shrinking aid.

What can we do in mid-term (1-3 years)? Pilot blended financing and co-funding models linking humanitarian response with private sector, diaspora, and development financing in selected sectors; Strengthen local NGO and government fiduciary capacity to meet compliance requirements, enabling gradual devolution of funding and decision-making; Formalise public–private–community partnerships to support continuity of essential services during funding gaps.

What can we do in long-term (3+ years)? Establish nationally anchored humanitarian financing mechanisms with diversified funding sources to reduce reliance on short-term external grants; Shift from emergency-driven programming toward shock-responsive systems integrated into national and sub-national service delivery; Embed domestic resource mobilisation and accountability reforms as part of long-term resilience and localisation strategies.

Question 2: How might Somalia reduce reliance on reactive, donor-driven humanitarian response and strengthen anticipatory action in a future where climate shocks, conflict, market volatility, and displacement increasingly interact, but early warning and decision-making systems remain fragmented, so that crises are anticipated earlier and community resilience is not repeatedly eroded?

What can we do in short-term (0-12 months)? Clarify institutional mandates and triggers for early action across government, humanitarian, and coordination structures to reduce delays; Improve interoperability and information sharing across existing early warning systems (climate, food security, displacement, markets); Build trust in early warning by strengthening risk communication at community level, using local languages and trusted actors.

What can we do in mid-term (1-3 years)? Integrate anticipatory action into national and state planning and budgeting, linking early warning signals to pre-agreed financing and response actions; Scale successful anticipatory action pilots, adapting them to different regional and conflict contexts; Invest in capacity for scenario analysis and stress-testing within national and regional institutions.

What can we do in long-term (3+ years)? Institutionalise foresight and horizon scanning functions within disaster management and humanitarian coordination systems; Develop cross-border and regional anticipation mechanisms for systemic shocks such as drought, displacement, and market disruption; Shift funding frameworks to make anticipation and early action the default, rather than an exception.

The consultation highlighted that Somalia’s humanitarian system is entering a period of heightened uncertainty, shaped by shrinking global humanitarian budgets, compounding climate and conflict risks, and increasing expectations for localisation and accountability. Participants agreed that the two prioritised foresight challenges: entrenched donor dependency and failure to anticipate systemic shocks are not isolated problems, but deeply interconnected structural issues that threaten both the resilience of institutions and the wellbeing of communities.

Through the foresight process, participants moved beyond reactive narratives and identified practical, future-ready priorities. These include safeguarding life-saving and resilience-building services amid funding volatility, strengthening local institutional capacity, clarifying decision pathways for early action, improving interoperability of early warning systems, and embedding foresight and anticipatory approaches within planning and financing structures. Importantly, participants recognised that no single intervention is sufficient; progress depends on sequenced actions, balanced portfolios, and sustained commitment across humanitarian, governmental, and innovation actors.

The workshop underscored the value of strategic foresight as a collective discipline, not a one-off exercise. Participants emphasised that anticipating future risks, diversifying financing, and protecting community coping capacity are essential to reducing repeated cycles of crisis response in Somalia. The outcomes of this consultation provide a strong foundation for shaping a national humanitarian research and innovation agenda that is locally informed, adaptive, and aligned with the realities of an increasingly complex humanitarian future.